When America joined the late 2010s global drift towards fascism many people commented that “at least” we’d see an upturn in angry protest music. The opposite has been true — artists are approaching the times with defeated songs aching with confusion and despair instead of blasting out venom. One recent album I think really works the best in tackling the issues of the day uses humor and distance to illustrate the new world we find ourselves in — Arctic Monkeys’ Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino, which I have spotlighted here.

Artistically, it can be problematic to be too specific in a protest song. The angry LP that I have been listening to with newfound appreciation the past couple of years has been David Bowie’s Scary Monsters.

With this 1980 masterwork, Bowie reacted to sharp turns to the right in the U.K. and U.S. but did so in a timeless, global, way. None of those bad vibes showed up in the studio as the album was said to have been recorded with good cheer and amiable working relationships. This dichotomy works its way into Scary Monsters itself as the album combines avant-garde noise and experimental recording techniques with keen pop instincts and more than a few echoes of early rock’n’roll. Unlike the Berlin trilogy, the uglier — though just as futuristic — sounds heard here offered old fans relief that Guitar Rock Bowie was back.

Art

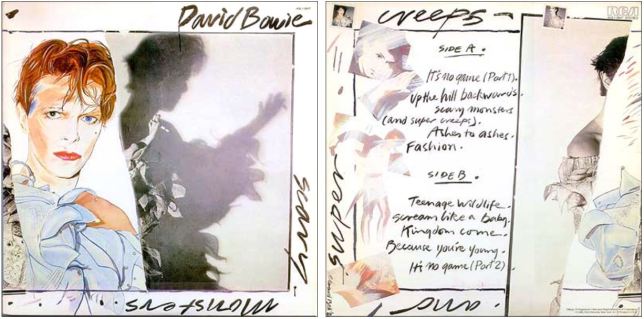

I can’t remember my father ever commenting on any other album sleeve I owned but he actively loved this one for Scary Monsters. This probably has to do with the Italian-French Pierrot harlequin painting on it and the way the photograph combines with 1940s Cat People style shadow imagery. Its a beautifully designed sleeve.

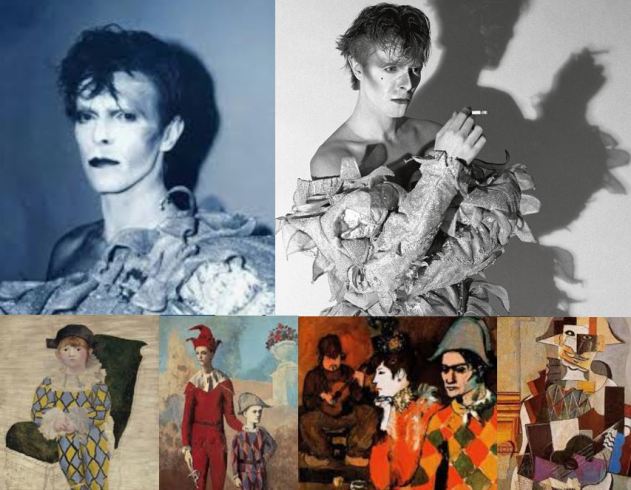

The paintings were done by Edward Bell, a fine artist who is still showing his work. Brian Duffy took the black & white photographs used in the overall sleeve collage that I believe Bell designed. Duffy’s photos are universally celebrated and offer up iconic imagery of Twiggy, Michael Caine, John Lennon, Terrence Stamp, and David Bowie, including what has become his career defining image, from the Aladdin Sane LP.

Many of Brian Duffy’s career defining snaps are from the 1960s. As a matter of fact, there is a documentary about his work and life titled Duffy: The Man Who Shot The Sixties that you can watch here.

Here is a photo Duffy took of Bowie that looks like it was captured on the set of The Man Who Fell To Earth but, perhaps, is from a couple of years later during the Berlin period.

The LPs front and back covers wrap-around each other, and have caused some confusion about what the actual title of the album is. The front cover lists Scary Monsters… and the back cover has …and Super Creeps. But, the album’s label and the promotional ads and reviews of the time list the album as simply Scary Monsters.

Here are Bell’s Pierrot style photos of Bowie along with a diverse set of paintings by Picasso, who seemed to like the subject. Tellingly, none of these clowns are happy or joyous — even the cubist one only looks to be in a pleasant mood — the harlequin wears an upturned mustache, not an actual smile.

Finally, the back cover includes painted images from Bowie’s previous three Berlin period albums. This works to both connect Scary Monsters to those most recent albums and, perhaps, get returning fans who stepped away from Bowie for a couple records to go back out and buy them.

Music

Tony Visconti has finally gotten his due as the single most important collaborator of David Bowie’s career. Of all the truly great Bowie albums these are the ones that Visconti did not take part in — Hunky Dory, Station To Station (where he was wanted but was off producing Sparks and Argent), and Let’s Dance. Bowie returned to working with his old friend with 2002’s Heathen and it can’t be a coincidence that this and his other final three albums are better than pretty much everything else he had cut since the early 1980s. The two seem to love working fast in the studio and crafting music that is often psychologically heavy with good humor and a lightness of touch. Bowie was easier to take as a “serious” artist because he could also be a self-deprecating “regular” guy.

I know I am far from alone in believing there is a strong line running from 1976’s Station To Station through to 1980’s Scary Monsters. Musically, this is a brilliant stretch of the art-rock avant-garde that has helped create the pop sound of today while remaining the sound of tomorrow. The album trajectory also starts with a dead-eyed pseudo celebration of Triumph Of The Will style imagery and ends with Bowie screaming at actual fascists.

Bowie’s working band of the era was still, blessedly, here — guitarist and bandleader Carlos Alomar, drummer Dennis Davis, and bassist George Murray. These three form a near perfect rhythm section, though tellingly, this album doesn’t really have much of the swing and sway that these three are masters at creating. Filling out the band are Robert Fripp, who shares beautiful-noise guitar duties with Chuck Hammer (who came up in the NYC free-jazz and pre-punk rock scenes). Andy Clark — from art-rock cult heroes Be-Bop Deluxe — plays synths and Roy Bittan, of the E Street Band, plays piano. The celebrity guest is Pete Townshend, who comes in to do his thing on “Because You’re Young.”

Bowie had also wanted Television’s Tom Verlaine — the guitar hero of the NYC punk movement — to play on the album. But, Verlaine was dropped when he took up hours of studio time tuning, and re-tuning, his guitar without ever being ready to record anything. Whether it was nerves or OCD that claimed him, Bowie and Visconti, preferred having musicians like Fripp who could walk in to the studio, listen to a track, and instantly come up with the perfect guitar part. “First impulse, best impulse” is something these guys took to heart, slowly down only when it was necessarily to get the exact sounds they wanted when they wanted them — as with the labored over “Ashes to Ashes.”

Ironically, Bowie’s Low, Heroes, and Lodger were considered un-commercial, non-rock art projects at the time of release but they don’t really sound all that out of place in the pop landscape of today. They were avant-garde yet often sound pretty — especially Low, which is just gorgeous. Upon release, Scary Monsters was embraced by critics, and fans, as Bowie’s return to actual rock’n’roll but today the album sounds much less mainstream. It is the avant-garde as ugly noise for ugly times.

Scary Monsters is, however, appropriately ugly. “It’s No Game” starts the album by lurching to life, putting screams over an atonal THUD that is counter-balanced by the cold comfort of a lovely, if lonely, Island of lounge guitar chords and melodic background vocals. Bowie had his friend Michi Horita powerfully restate his lyrics in Japanese in an apparent attempt to counter entrenched sexist attitudes about passive females. The intersection of Bowie’s atonal, shotgunning anger, Horita’s more controlled declarations, and Fripp’s insane metal machine music guitars all leads to our David screaming “Shut Up!!!”

The sonic and psychic elements of “It’s No Game” repeat themselves in most of the album’s songs though the next tune, “Up The Hill Backwards,” sounds almost blissfully 1960s in comparison. Its more of a zen acceptance of bad things rather than positivity, though, as an era of new found freedoms gives way to reactionary forces and repression. “Up The Hill Backwards” is the most pleasant, positive song ever to state “We are legally crippled/It’s the death of love.”

“Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps)” ups the squall of the brilliantly eccentric lead guitars while keeping the more mainstream rock feel of the previous track. Three different songs and three completely different lead vocal approaches — this one features Bowie as a lovable, Artful Dodger Cockney/Mockney type — Michael Caine’s witty Alfie placed in the middle of an arty Italian horror/suspense film.

“Ashes To Ashes,” like “Sound and Vision” and “Heroes,” before it, now sounds like an utterly brilliant pop song. But, when it came out in 1980, “Ashes to Ashes” sounded like nothing you’d ever heard before — the Punk era equivalent of The Beatles “Tomorrow Never Knows.” The zen calm choruses are countered by the half-desperate verses echoing into eternity. “Ashes To Ashes” is kind of an “answer song” going back to “Space Odyssey” — not dissimilar to how The Beatles “Glass Onion” brings up other Fab Four tunes.

“Ashes to Ashes” was a big hit in Europe, as was the next track, “Fashion,” which ends the first side. A dance stomper that has fun combining fascism and xenophobia with fashion and trendiness, this one proves that the sonic ugliness on much of Scary Monsters can be tamed into a mainstream hit (at least outside the USA of 1980). Fripp’s guitar work here sounds almost like someone cutting through sheet metal with a chainsaw.

As much fun as Bowie was having making Scary Monsters he must have been feeling some sort of paranoia about his career and his place in the music industry. He was only in his early 30s here, but, as side 2 opener “Teenage Wildlife” attests, he felt like an elder statesman to a bunch of hungry kids who looked at their super Bowie fan status as permission to hunt him down and replace him. “Teenage Wildlife” puts a retro, good time rock’n’roll framework behind what is essentially a melody-free rant done by a malfunctioning robot crooner who is painfully morphing into organic life. Once again, Bowie bravely breaks all of the rules of professional singing (and pitch) but it works perfectly for this song. This one didn’t do much for me at age 12 but as I grew older I connected with it. A more romantic counterpart to this can be heard in “Because You’re Young,” which is both much catchier and less epic and powerful than “Teenage Wildlife.”

“Scream Like A Baby” takes us back to the fascist dystopias found on Side A. The lyrics, and arrangement, were changed from an old tune called “I Am A Laser” that Bowie had written for a group his then-girlfriend, Ava Cherry, was in. Song wise the verse is a lot catchier and better written than the stomping chorus. A cover of Tom Verlaine’s “Kingdom Come” offers up some relief even if its protagonist is also stuck in a prison — here at least, there is the hope of salvation. Both versions of “Kingdom Come” have a rare mix of mellow good vibes and tense, unsettled emotions. If anything, Bowie’s version has more ethereal guitar sounds and a dreamier vibe — elements that would develop further in Verlaine’s own work. Bowie’s weird, warped retro-futurist rockabilly crooner vocals make their last appearance on the album here.

“It’s No Game” returns at the end, infinitely calmer with all of the sonic ugliness stripped away. Bowie’s matter-of-fact vocal delivery make the words stand out more. The lyrics make plain that fundamental decency is gone and that WWII era, Soviet style, or Third World randomly violent horror can be just around the corner for everybody. One of the lyrics to “It’s No Game” state “Put a bullet in my brain and it makes all the papers.” That horrible event didn’t happen to Bowie but it almost did — only he found out about it after the album was recorded. When a maniac murdered John Lennon the police immediately visited David Bowie — he was on the maniac’s hit list.

The murder of John Lennon, Bowie winning full-time custody of his son, and an offer to play The Elephant Man on Broadway stopped any planned tour or even any promotional concerts around Scary Monsters.

While the reviews Scary Monsters received were largely very positive David Bowie earned the biggest positive press of his entire career for his work in The Elephant Man, which he performed without changing his basic appearance with makeup or prosthetics. Bowie did make music videos for a couple of the singles here, most famously for “Ashes to Ashes,” but it was still a couple years away from MTV to make a difference in America. That would change in perfect lock-step with 1983’s Let’s Dance. Bowie did appear on The Tonight Show to promote the album with Johnny Carson once again illustrating why he was the classiest act on television.

Still, what Scary Monsters had going for it commercially were two singles, “Ashes To Ashes” and “Fashion,” that could have been huge everywhere. The album did top the charts in many European countries, including the UK. But a very respectable No. 12 in the USA didn’t even result in Silver status for an album that was locked out of mainstream radio outside of Boston and Los Angeles, where KROQ was on-the-cusp of defining alternative rock for the next two decades.

But, the relative outsider-ness of the Berlin Trilogy and Scary Monsters ended up helping Bowie more than hurting him. The sounds of the 1980s were all created in the 1970s and Bowie was a big part of that — I’d say the biggest part of that, along with Roxy Music. Even the brilliant “Heroes,” which in the 21st Century is Bowie’s most streamed song, was a non-starter as a single in 1977.

Glam era Bowie ended up influencing punk —Diamond Dogs offering up a scarred punk landscape before such a thing was actually codified in popular culture. You can also link the polite, but emotionally twisted, English soul of Young Americans to both the original New Romantic Blitz kids and the sophisti-pop glamor sides of Spandau Ballet and Duran Duran. Likewise, you can hear the stark European guitar rock of Station To Station and the more futuristic Low transformed by the likes of Gary Numan and John Foxx into synth-pop. Take the instrumental finesse out of “Blackout” or take Bowie and Iggy’s “Nightclubbing” just as it is and you get post-punk with Joy Division and Public Image Ltd. Bowie doesn’t yet seem to pleased with this influencer status on Scary Monsters — its probably no surprise that Let’s Dance and a massive stadium tour were around the corner.

Unlike Kraftwerk, who embraced the future enthusiastically, Bowie was more than a touch skeptical of humanity’s essential worth and the direction we were heading in. “Sound and Vision” is about drifting away into a perfect blue sky and not about plugging into the matrix. That disengagement from pain, and the wider world, is different from ironic detachment. In person, Bowie made jokes and charmingly laughed off adversity — very much in the English manner of his generation — while his songs screamed “To be insulted by these fascists…it’s so degrading.” That is worlds away from Kraftwerk’s love songs to pocket calculators and people becoming one with their bicycles.

Joy Division barely made it into the 1980s, but, like Scary Monsters, and the Bowie albums that came before it, they kept getting played — and heard — by more and more people through the coming decade(s). Whereas “Ashes to Ashes” and “Fashion” were too weird for mainstream America in 1980 they now play on radio station’s across the country. As the music critic Rob Sheffield has noted, these nostalgic new wave radio weekends are a staple for aging listeners who actually didn’t listen to any of this music when they lived through the 1980s — we have rewritten our collective histories. It kind of reminds me of how barely anyone was actually a hippy in the 1960s but in the 1970s small towns were overflowing with men with long hair and beards.

What is impressive is that Scary Monsters hasn’t really lost any power even as its sonic innovations — once a revelation by themselves — no longer shock or surprise. If you want to process today’s disgust, anger, confusion, disappointment, and teetering hopes just slip this 40 year old album onto your turntable. Hopefully it won’t need to stay there too long.

— Nick Dedina

4 thoughts on “David Bowie, Scary Monsters”